List of Contents

Key points

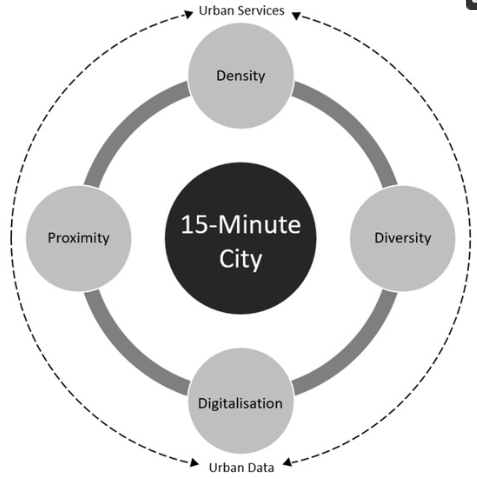

- The 15-minute city is built on four core principles: proximity, diversity, density, and ubiquity, aiming to ensure that all essential services are within a 15-minute walk or bike ride.

- COVID-19 accelerated this model by highlighting the need for local, self-sufficient neighborhoods.

- Smart technologies like IoT and digital infrastructure help optimize service delivery and urban planning.

- Cities like Paris, Melbourne, Shanghai, and Barcelona have adapted the concept to fit their local contexts, focusing on livability, sustainability, and resilience.

15-Minute City Concept

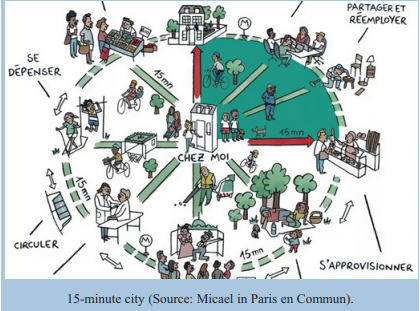

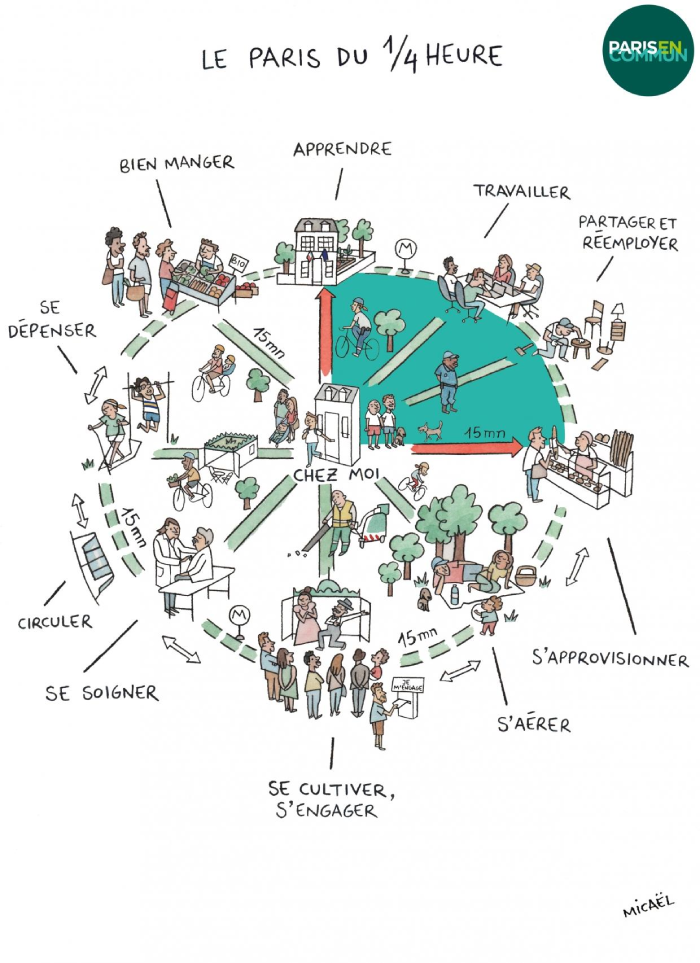

The central idea of the 15-minute-city is that residents should be able to access workplaces, schools, healthcare, recreation, shops, and cultural spaces within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from their homes. Rooted in the principle of chrono-urbanism, this approach reframes the organization of urban space based on time rather than distance, arguing that proximity and accessibility should shape city layouts more than vehicle traffic flow.

Moreno outlines four core principles of the 15-minute city—proximity, diversity, density, and ubiquity—as key to enhancing urban livability. These principles call for:

- Proximity: Ensuring all essential urban functions are within walking or cycling distance.

- Diversity: Promoting social, functional, and architectural variety to foster vibrancy and multiple uses for urban elements.

- Density: Designing for an optimal population density that ensures efficient service provision and resource use, without overcrowding or under-utilization.

- Ubiquity: Guaranteeing the equitable distribution of services and infrastructure across the entire urban geography.

In terms of density, the 15-minute city concept espouses that cities should have an optimal number of residents. This assumption thereby ensures that it is possible to facilitate quality resource and service provision, without over-consumption or under-utilisation.

The ubiquity principle advances the need for 15-minute cities’ requirements to be in large supply in all geographies, thereupon making them available for everyone and at an affordable cost. This aspect will greatly benefit from the deployment of advanced technologies such as IoT (Internet of Things), Digital Twins, and 6G networks. These technologies can support urban planners in contextualising and implementing tailored 15-minute city models, ensuring that variations in geography, culture, and local needs are properly accounted for.

For instance, Paris is already leveraging data and technology in its goal to reduce private car use by 50%, while promoting cycling by expanding bicycle lanes across the city. Similarly, Bellevue is incorporating 15-minute city principles into its Environmental Stewardship Plan 2021–2025, demonstrating the feasibility of integrating emerging technologies into sustainable urban planning.

Such urban transformation requires reallocating space from cars to people. Sidewalks, cycling infrastructure, open-air communal areas, and adaptive reuse of public spaces (like school playgrounds for recreation or parking during off-hours) are central to its implementation.

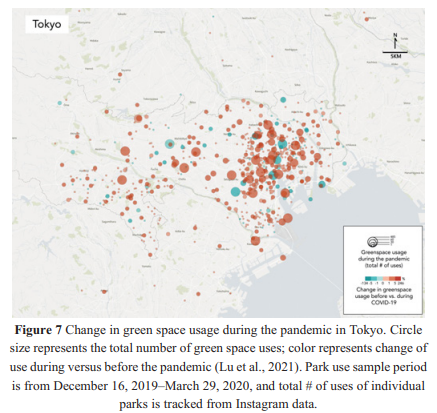

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the urgency of this approach. As public transit systems experienced a dramatic decline due to infection concerns, the need for walkable, self-sufficient neighborhoods became more apparent. Urban mobility trends shifted, with many cities investing in cycling lanes, pedestrian paths, and flexible infrastructure to support active transportation and local living. These dynamics validate the long-term relevance of the 15-minute city in enhancing resilience, public health, and environmental sustainability.

The Role of COVID-19 in Advancing the 15-Minute City

The pandemic fundamentally reshaped urban mobility and public perception of space. Public transport systems, once considered essential to sustainability, experienced sharp declines in ridership due to fears of contagion. This shift had cascading effects:

- Declining revenues forced transit agencies to cut services;

- Increased operational costs were incurred to meet hygiene standards;

- Car ownership rose in many cities, reversing years of emissions reduction progress;

- Remote work and online services became normalized.

In response, many cities around the world implemented emergency measures aligned with the 15-minute city logic:

- Temporary bike lanes and pedestrian zones;

- Redistribution of street space;

- Enhanced support for active transport and local commerce;

- Land-use changes favoring mixed-function neighborhoods.

These trends suggest that future urban resilience depends not only on technical infrastructure, but also on fostering self-sufficient, walkable communities that minimize reliance on centralized services and long commutes.

The 15-Minute City via the Smart City Network

One of the key dimensions of the 15-minute city is digitalization. This involves the use of digital technologies to influence how the city functions, delivering services and providing value-producing opportunities across various urban systems and domains. These domains encompass the overall landscape of the 15-minute city, including its underlying components such as ICT infrastructure, built infrastructure, green/blue infrastructure, transport infrastructure, energy infrastructure, economic infrastructure, and social infrastructure. Within this context, the focus is primarily on ICT infrastructure and built infrastructure, given their particular relevance to the dimensions of the 15-minute city.

Built infrastructure refers to “the patterns of the physical objects in the city pertaining to the built-up areas as well as those areas planned for new development and redevelopment… The compact and ecological dimensions of urban design characterize most of the built infrastructure in terms of buildings, blocks, streets, open space, public space, green space, and essential infrastructure.” This aligns with the core strategies of the compact city and eco-city models, such as density, diversity, and proximity, all of which are also key characteristics of the 15-minute city.

ICT infrastructure enables the 15-minute city to transition into a data-driven form of urbanism by leveraging advanced data and information technologies to entirely transform urban processes. This includes evaluating, analyzing, re-engineering, and re-imagining how urban infrastructures and services are designed, developed, managed, and planned in line with sustainability goals.

ICT infrastructure digitally comprises the components that power the technology embedded throughout the city, such as sensors, smart devices, systems, software programs, networks, data storage facilities, data processing platforms, cloud and fog computing, policies, and standards. These technologies permeate urban life, providing support for city management. To coordinate the many different components that comprise the digital dimension of the 15-minute city requires a stronger function of intelligence. This intelligence brings together what governments and businesses offer in terms of engaging service users and communities, providing hardware, software, and solutions that enable “smartness.”

The Role of IoT and Urban Computing in Smart Cities

IoT (Internet of Things) has emerged as the predominant paradigm for urban computing and intelligence. This marks a shift from ubiquitous computing towards a deployable model that fosters city analytics, powered by big data analytics. The proliferation of wireless communication technologies facilitates the creation of dense, multi-faceted IoT networks across urban areas, leveraging sensors that enhance communication capabilities and data transfer.

The 15-minute city, as a novel urban concept, uses IoT to achieve its sustainability goals by integrating density, diversity, and mixed land use strategies. Through IoT, cities can improve land use efficiency, promote resilient urban communities, reduce per capita energy usage, lower infrastructure demands, and ultimately reduce pollution. These interconnected systems form a large-scale digital ecosystem that enables services for sustainable urban living.

Architectural Layers of IoT in the 15-Minute City

The IoT architecture in the 15-minute city is typically organized into four key layers:

- Physical/Perception Layer: This layer includes urban sensing and data acquisition through various types of sensors. These sensors collect data on mobility, traffic, energy, and other environmental factors across the city. Examples include RFID tags, smartphones, GPS, and other digital platforms that generate real-time data.

- Network/Transmission Layer: Data collected from the physical layer is transmitted through various wireless networks, such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and 4G/5G cellular networks. These networks facilitate continuous data flow from urban sensors for further processing and analysis.

- Middleware/Technology Layer: This layer provides a communication interface between the physical and application layers. It organizes and centralizes the data collected from the sensor network, making it available for further processing. Middleware also manages the distribution, interoperability, and scalability of computing resources within the IoT system, empowering distributed processing and supporting urban computing.

Application/Service Layer: This layer transforms the data collected and processed in the lower layers into actionable knowledge. It provides applied intelligence services, such as real-time analytics, predictive models, and decision-support systems for various urban domains. The services are typically based on big data analytics, including diagnostic, descriptive, predictive, and prescriptive types, enabling smart solutions for urban management and planning.

15-Minute City Paris

Paris is widely recognized as the flagship implementation of the 15-minute city model. Under Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s leadership (2020–2026), the French capital integrated the model into its urban policy framework, advancing it as a core component of its post-pandemic recovery and climate action strategy.

The “Ville du quart d’heure” initiative restructured neighborhoods to encourage hyper-proximity, reduce car dependency, and foster urban regeneration through participatory governance. Key interventions include:

- The pedestrianization of districts;

- Creation of school streets and safe zones around educational institutions;

- Transformation of schoolyards into public “climate oases”;

- Installation of open-air libraries and shared recreational areas;

- Launch of a bioclimatic local urban plan empowering neighborhoods with decision-making capacity on housing and revitalization.

Citizen involvement is central to this process. Participatory budgeting, volunteer programs, and neighborhood kiosks ensure residents can shape and contribute to local transformations. Paris’s model has thus become a blueprint for balancing climate justice, equity, and livability.

15-Minute City Melbourne (20-minute neighourhood)

Melbourne’s adaptation of the concept—branded as the “20-minute neighbourhood”—shares the foundational goal of local living. The city’s strategic plan (Plan Melbourne 2017–2050) emphasizes equitable access to key services within a short walk or cycle, enhancing well-being while reducing emissions.

COVID-19 served as a catalyst for rapid change. As movement restrictions limited long-distance travel, the value of hyper-local amenities and resilient neighborhood design became evident. The city responded by:

- Expanding green open spaces;

- Building new cycle infrastructure;

- Supporting mixed-use zoning to accommodate retail, health, and social needs locally;

- Encouraging remote work as a tool to decentralize urban mobility.

The Melbourne case illustrates how the 15-minute city model can be tailored to regional needs while promoting sustainability and social cohesion.

Shanghai 15-Minute City

Shanghai’s “15-minute community life circles” represent a uniquely localized interpretation of the concept, emphasizing both physical and digital accessibility. In line with its 2035 Master Plan, the city aims to provide comprehensive services—including elderly care, education, healthcare, commerce, and leisure—within each neighborhood.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, these life circles proved essential in limiting the spread of the virus while maintaining functional urban life. The city invested in smart infrastructure and spatial justice, ensuring that even marginalized communities could rely on nearby services.

Shanghai’s approach demonstrates how the 15-minute city can be realized in a megacity context, combining digital governance, high-density planning, and public health considerations.

Barcelona 15-Minute City

Barcelona applies the principles of the 15-minute city primarily through its Superblocks program (Superilles), which reconfigures city blocks to limit vehicular traffic and prioritize public space.

COVID-19 accelerated these plans:

- More than 500 streets were temporarily adapted to prioritize pedestrians and cyclists;

- Public spaces were transformed into green corridors and community hubs;

- New bike lanes and traffic calming measures were introduced;

- Curb space was reallocated to facilitate outdoor commerce and community engagement.

Barcelona also developed a “proximity services” framework that emphasizes equitable distribution of healthcare, education, and cultural amenities. This ensures that every neighborhood can function autonomously, reducing both traffic and emissions.

References

Coordinating Lead Authors

- Darshini Mahadevia, Ahmedabad University, Ahmedabad

- Gian C. Delgado Ramos, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City

Lead Authors

- Janice Barnes, Climate Adaptation Partners and the University of Pennsylvania, New York/Philadelphia

- Joan Fitzgerald, Northeastern University, Boston

- Miho Kamei, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Hayama

- Kevin Lanza, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin

Contributing/Case Study Authors

- Zaheer Allam, University of Paris, Paris

- Amita Bhide, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

- Yakubu Bununu, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria

- Didier Chabaud, University of Paris, Paris

- Amitkumar Dubey, Ahmedabad University, Ahmedabad

- Yann Francoise, Climate and Ecological Transition Directorate at Paris City, Paris

- Saumya Lathia, Ahmedabad University, Ahmedebad

- María Fernanda Mac Gregor-Gaona, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City

- Carlos Moreno, Paris 1 Sorbonne University, Tunja/Paris

- Marie-Christine Therrien, Ecole Nationale d’Administration Publique – Cité-ID LivingLab Urban Resilience Governance, Montreal

- Nada Toueir, Lincoln University, Montreal

- Nelzair Vianna, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Salvador

Element Scientist

- Melissa López Portillo-Purata, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City

The Role of COVID-19 in Advancing the 15-Minute City

- Mahadevia D, Delgado-Ramos GC, Barnes J, et al. Learning from COVID-19 for Climate-Ready Urban Transformation. Cambridge University Press; 2025.

- Allam, Z., Bibri, S. E., Jones, D. S., Chabaud, D., & Moreno, C. (2022). Unpacking the “15-Minute 1City” via 6 G, IoT, and digital twins: Towards a new narrative for increasing urban efficiency, resilience, and sustainability. Sensors, 22(4), 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22041369

- Bilbao, B., Steil L., Urbieta, I. R., Anderson, L., Pinto, C., Gonzalez, M. E., Millán, A., Falleiro, R. M., Morici, E., Ibarnegaray, V., Pérez-Salicrup, D. R., Pereira, J. M., & Moreno, J. M. (2020). Incendios forestales. In J. M. Moreno, C. Laguna-Defi, V. Barros, E. Calvo Buendía, J. A. Marengo, & U. Oswald Spring (Eds.), Adaptación frente a los riesgos del cambio climático en los países iberoamericanos: Informe RIOCCADAPT (pp. 459–524). McGraw-Hill.

- Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006

- Parreño-Castellano, J., Domínguez-Mujica, J., & Moreno-Medina, C. (2022). Reflections on digital nomadism in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic – effect of policy and place. Sustainability, 14(23), 16253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316253

15-Minute City Paris

- Pisano, C. (2020). Strategies for post-COVID cities: An insight to Paris en Commun and Milano 2020. Sustainability, 12(15), 5883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155883

- Carlos Moreno. Droit de cité: De la “ville-monde” à la “ville du quart d’heure”. Editions de l’Observatoire, 2020.

15-Minute City Melbourne (20-minute neighbourhood)

- Gunn LD, Rozek J, Hooper P, Lowe M, Arundel J, Higgs C, Roberts R, Giles-Corti B. Creating liveable cities in Australia: A scorecard and priority recommendations for Melbourne. Melbourne: RMIT University, Centre for Urban Research, 2018.

- Badawi, Y, Maclean, F, and Mason, B, (2018). The economic case for investment in walking, Victoria Walks, Melbourne.

15-Minute City Shangai

- Urban Planning Society of China. (2022). Urban Community Renewal Practice from the Perspective of “New Urban Agenda”. 15-minute community life circle in Shanghai.

15-Minute City Barcelona

- Marquet, O.; Miralles-Guasch, C. The walkable city and the importance of the proximity environments for Barcelona’s everyday mobility. Cities 2015, 42, 258–266.

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-Minute City Lens: Mapping the Accessibility and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities5010010